Archival material held at the British Museum (BM) reveals that staff recruitment was a fairly bureaucratic, rule-driven process over which considerable trouble was taken, certainly compared to many non-national museums where recruitment was ad hoc, informal, and concerned with spending as little money as possible above all else. Although museums have changed their recruitment practices significantly and recognise the problematic nature of historic practices, it is worth drilling down into rationales at the BM in the 19th and 20th centuries, because the continuities as well as the changes between historic and contemporary practices are striking.

‘The peculiar service of the British Museum’ [1]

In the early 1930s the BM recruited new staff to fill Assistant Keeper roles in a number of departments, and files in its archives tell us quite a lot about recruitment and selection. Recruitment was only to the post of Assistant Keeper, candidates had to be between 22 and 26, ‘natural-born’ British subjects, of good health and character, and, if female, unmarried or widowed.

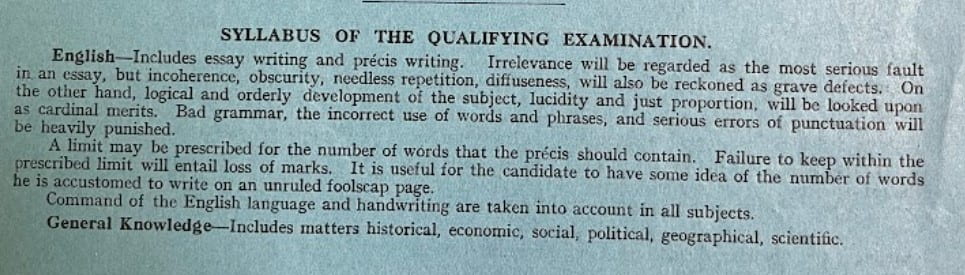

The selection process consisted of an application form with references, an examination, and an interview. Examinations were held as often as needed and only those who had passed it could apply for Assistant Keeper roles. The exam tested quality of general education rather than anything subject specific, and was the same for all departments, as the syllabus below shows. This examination, however, was in general abolished for museum recruitment in 1932; it didn’t seem to help with the selection of the best candidate, and certainly most of the successful applicants did not come top in their batch of examinees, though they all reached a pass standard. Moreover, degrees and academic qualifications were becoming more important than such general knowledge.

Figure 1: Regulations for the Competitive Selection of Assistant Keepers (Second Class) in the British Museum. Principal Trustees’ Papers, Appointments and Recruitment 1929-1932 File, BM

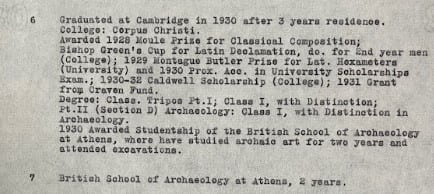

Application forms show that more specific alignment with particular departments might be sought in terms of education and previous employment; it can be seen that the successful 23-year-old candidate for the Assistant Keepership in Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities had not only classical literary credentials, but also experience with archaeological excavation (both were stressed in the summary of his application). His examination result was lower than two other unsuccessful candidate, and he did especially weakly in the English section, although he did pass the exam.

Figure 2: excerpt from summary of candidate for Assistant Keepership as part of selection pack for interviewers

The interviews themselves were very short, with just ten minutes between the interview time of each candidate, and undertaken by one representative of the Civil Service Commission and two representatives of the museum. Thereafter the successful candidate had to pass a medical examination – this was not an insignificant process and at least two successful candidates had job offers withdrawn on medical grounds in just two years between 1930 and 1932.

This archival material on recruitment and selection both tells us some significant things about national museums and the barriers to working in them, and hides other things which remain tantalisingly beyond our reach. The ten-minute interviews, above all, are closed books to us and to all those who weren’t in the room at the time. This is particularly frustrating because, as noted, selection generally did not align with performance in the exam, with high-performing female and Jewish candidates losing out to lower-scoring male candidates, raising the suspicion that interviews were largely a fig leaf to cover recruitment practices designed to produce new Assistant Keepers in the mould of existing ones. This was undoubtedly true to an extent but, paradoxically, the minimal role played by the exam was also because the museum didn’t trust civil service recruitment procedures and valued more specific experience. Being part of the civil service and being concerned to protect the excellence and uniqueness of the institution had existed in tension in BM recruiting practices since the middle of the nineteenth century as I explore below; both clearly favoured very narrow types of educational achievement, social background and category of employee, though they represented a different type of selection to previous practices and were seen as meritocratic, as opposed to patronage-based earlier.

Professionalising museum recruitment: the Civil Service

The examination was an inheritance from the BM’s Civil Service past, and had always been controversial among its staff. Antonio Panizzi (1797-1879), who was Principal Librarian (the director or head of the institution) of the BM from 1856 to 1866, was both in some ways responsible for the introduction of the exam, and the fiercest critic of it. He campaigned strenuously and successfully for museum employees to be granted pensions (which they had hitherto not received), on the same basis as other civil servants – but an unintended consequence was that, like nearly all other civil servants following the Northcote-Trevelyan report of 1854, potential employees had to pass an exam to provide an ‘objective’ measure of their merit. [2]

Panizzi was extremely irritated by the nature and outcomes of the exams, which were taken by all including attendants; but particularly by those for potential assistant keepers, which scrutinised spelling, knowledge of literary history, and other subjects designed to indicate a good general education. He argued – at length and repeatedly – that they failed to test adequately practical and subject-specialist knowledge, letting in those who were incompetent and rejecting excellent candidates. He wrote extensively and in scathing tones to the Civil Service Commissioners about how unsuitable the general selection practices of the Civil Service were for the museum, and argued for greater involvement of museum managers in the process, and that possession of a degree ought to exempt candidates from examination. [3]

Before the 1850s, recruitment to positions at the BM was largely by patronage; people such as Panizzi himself, and his arch-rival Frederic Madden, owed their jobs to advocacy by political figures and/or wealthy, aristocratic collectors. They were not unqualified, mostly graduates with strong interests in their field and various levels of experience, but they still needed to have the ear of someone who could convince the Trustees to hire them. And many of the people whose positions derived from this system, described by Andrea Geddes Poole, in her book on cultural authority in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain, as ‘gentlemen amateurs’ [4], continued to work throughout government offices at least until the early 20th century. But though the era of patronage was thereafter replaced by an ostensibly merit-based objective system, the Civil Service was still apparently not able to deliver employees with the right skills for the museum, because the civil service valued mobile, generalist employees who could turn their hand to work in any department.

Relationship with the civil service had a strong influence on employment at other UK national museums and galleries; Poole has shown that between at least 1890 and 1939 the Treasury had total control over appointments (and dismissals) at the National Gallery; it used this influence to bring the Gallery more into the structures of the reformed civil service, and to remove it from the influence of ‘amateur connoisseur’ aristocratic patrons who had exercised so much cultural authority before state apparatus developed. [5]

However, the Treasury itself over this period was dominated by high-flying Oxbridge graduates, potentially a slightly more meritocratic but no less exclusive group. They staked their claim to lead cultural institutions on their elite education and ‘professionalism’ – a professionalism distinct from that developed at the provincial museums of the period.

This process whereby recruitment apparently moved towards recognising genuine ability, but nevertheless continued to privilege a small group of people (white, male, able-bodied and exclusively from the upper middle classes) reveals the power of education to reproduce inequalities – and particularly, I would suggest, the power of the idea of educational excellence. Leading staff at the BM always thought of their institution as excellent, and in seeking to maintain this excellence created a highly exclusionary organisation.

The classical education ideal

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth century, the ideal of classical education dominated BM recruitment. This was both because of civil service reforms, and because of the nature of the museum. The classical education ideal essentially reflected curricula at the leading public schools and Oxford and Cambridge, and so inequality was inherent in it, though rendered invisible through the formation of the ideal. This comes into view through discussions in the 1960s about careers dissatisfaction among curatorial staff. The BM’s commitment to recruiting such staff young (straight out of university if possible), attributable to their sense of the distinctive excellence of their organisation and resulting need to form curatorial staff into BM men, meant that, according to some, keepers were of poor quality and promotion was out of reach for many assistant keepers.

Some of the Trustees, notably Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1890-1976), the outspoken archaeologist, were keen to change recruitment practices. Wheeler, who had become a Trustee in 1963, argued just a few years later that the man who impressed at 23 might prove to be entirely unsatisfactory in later life – and indeed he alleged that there were 3 senior staff who were ‘wholly inadequate’ and ‘professionally notorious’. Wheeler was in favour of opening up the routes through which people could access a BM career. This was partly special pleading – he thought experience of archaeological fieldwork was a good step after graduation and before museum work, which is precisely what he had done, and he was a persistent critic of the BM, going so far as to describe it as a ‘mountainous corpse’ [6]– and was not received well by existing keepers.[7]

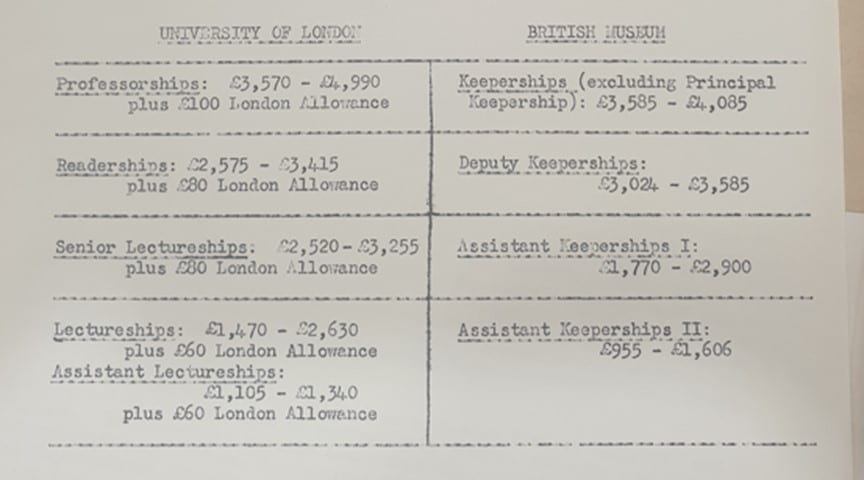

Departmental keepers maintained the belief that the only way to train a keeper was by recruiting the best young Oxbridge graduates as soon as they graduated and shaping them over their whole career, rather than bringing in ‘outsiders’, however brilliant, at later stages, or relying on the Museums Association diploma as a qualification for working at the BM; this was rejected out of hand. The closest comparison to a BM career that could be found was an academic one, with lecturer/professor salaries compared to BM ones.

Figure 3: comparison of salary scales at the University of London and the British Museum, BM Committee on Recruitment, 1965-68

Thus all those involved in the debate were convinced that the way their own careers had developed was the way to ensure the highest calibre of recruit, while believing that other routes delivered lower-quality employees – an obvious mechanism by which barriers to recruitment for anyone different were maintained.

Thus, 20th-century recruitment at the BM was still marked both by 19th-century civil service ideals, and by a sense of the institution as unique and excellent. Attempts to professionalise recruitment, so that it reflected merit rather than gentlemanly connoisseurship and patronage, only served to create privileged access for a different group – those with Oxford and Cambridge degrees, youth, health, and the connections to get experience in settings such as the various British Schools abroad.

The British Museum historically always had a significantly different approach to recruitment and selection from other museums, particularly civic museums but even from other national museums as they developed. Although unique in many ways, it is significant because it employed more people in all sorts of roles than any other museum, at least up to the start of the twentieth century, and because it had among the longest traditions of recruitment. Its status as the ‘gold standard’ of museum work exercised a profound effect well beyond its walls. Its archival recruitment archives are, accordingly, different to those of other museums; for all their silences and formality, they have much to tell us, not least about how loyalty to a perceived excellent institution can create extremely constrained and unequal recruiting practices.

Notes

[1] Correspondence between Civil Service Commissioners and Principal Librarian of the British Museum Respecting Examination of Candidates for Situations, House of Commons Papers 1866, p. 9

[2] Edward Miller, That Noble Cabinet: A History of the British Museum, Andre Deutsch 1973, p. 249

[3] Correspondence between Civil Service Commissioners and Principal Librarian of the British Museum Respecting Examination of Candidates for Situations, House of Commons Papers 1866, p. 31

[4] Andrea Geddes Poole, Stewards of the Nation’s Art: Contested Cultural Authority 1890-1939, University of Toronto Press 2010, p. 11

[5] Poole, Stewards, p. 59

[6] Jacquetta Hawkes, Mortimer Wheeler: Adventurer in Archaeology, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1982, p. 333

[7] BM Committee on Recruitment 1965-8 file, 6 June 1966, letter from Sir Mortimer Wheeler to Lord Radcliffe

All images are reproduced with permission of the British Museum. Many thanks for Francesca Hillier, Senior Archivist at the British Museum for her help and knowledge